Originally published by Mo on Gaming as Women, September 28, 2015

Act One: In Which I Am Changed

Anyone who knows me knows I’m a little obsessed with women’s history, particularly when it comes to the role of women in WW2. And anyone who reads me on GAW knows that I am particularly interested in the Hx/Relationship/Bond mechanics in Powered by the Apocalypse games and how they related to gender socialized play.

So when Jason Morningstar asked me to consult for him as he was fine tuning Night Witches, I was all in. As a thank you, he gave me a gift that he would later offer backers of the Kickstarter: a portrait of me (done by GAW’s own Claudia Cangini), in a Nachthexen uniform. This delighted my inner history geek! But I didn’t realize then how important that it would become to me.

As part of the campaign, a deck of cards was produced to enhance the experience of the game. In it, were plane diagrams, medals, ceremonial dedication speeches…. and portraits of sample Night Witches, new ones plus all of the portraits that had been commissioned for the Kickstarter – including the consultants.

Once Night Witches fulfilled, people started posting pictures, of their books, of the cards, and of their games. As I came across those posts on social media, I would often get a moment of cognitive distortion when I noticed my portrait was on the table in people’s game set up. There I was: a Hawk. There I was: a Pidgeon. There I was: a Raven.

People were picking me as the visrep of the person they wanted to be in their game.

Now, I’m a woman living in the age of media-mandated perfection. And as such, I’m subject to the cruel and usual punishment of the Beauty Industrial Complex. I have not – just like every woman (and most men) I know – come through life without a complicated relationship with my appearance. I think most women, secretly or openly, whether they are beautiful or not, spend a lot of time hating on their bodies. We look into mirrors and see all the ways we fall short.

But here people were, picking me to be what they wanted their character to looked like.

And then this happened:

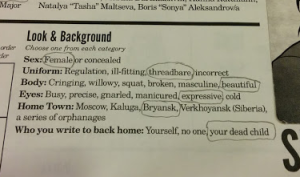

Someone posted their character sheet with me as their Sparrow. In the options under Body, they circled “beautifulâ€.

I can’t quite articulate what happened then, but it feels in my memory like that cartoon moment when the Grinch’s heart which is three sizes too small suddenly is pictured expanding so big it takes over the square it’s confined in. And between this lovely thank you gift and this innocuous social media post, I have – even if only a little – changed how I feel about my own body. In the moment that my picture and that option were chosen together by someone far away, the two ceased to be incompatible by default.

And that right there is both the power of representation, and the power of role-playing games as a medium to provide unique and innovative ways to make representation matter more.

Act Two: In Which We Need to Change Things for Others Too.

Games are our dreams. Stories are the way we make sense of our lives, and understand our place in the world. Seeing myself in a game made me dream about myself differently. And sure, this is a pretty specific example: It’s specifically an image of me, and specifically coded in a way that will drive the point home. But we don’t need to go so far to have exact pictures of ourselves to feel represented. In fact, short of actual portraits of ourselves, detail can get in the way. Scott McCloud talks about this idea in Understanding Comics: The less detail a character on a page has, the more a reader can project themselves into their place in the story. Our minds differentiate and create distance from characters by difference: when we see something that is not us, we categorize and say this is me and that is not.

![]()

I’m a white cis woman. While there are a lot less white cis women in game art then there are white cis men, there are a lot of white cis women too. Few of them look anything like me. They conform much more magically to the strange and terrible demands of the Beauty Industrial Complex, often even where those demands include the need for anti-gravity technology or spinal surgery.

The art in game books include enough things that aren’t me to make my brain trigger distance. People who look like me do not exist in this game. But the art in game books include enough things that are me to make my brain trigger proximity too: I see white faces, female faces, cis people. They read: the people in this game are more beautiful versions of me. That might not be the best thing, but it’s a place we’d all like to escape to.

But if I’m not white, or I’m trans, or I’m otherwise absent in the visual field, all the game says to me is absence. This is not a place for you, you are not here.

I’d really like everyone engaging with games (and other media) to have equal opportunity to dream themselves beautiful.